In The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus dwells on the fact that Sisyphus - punished to push a rock up a hill for all of eternity - must actually be seen as happy. For Camus, the fact that Sisyphus is forced to do something isn’t the important part. What is crucial is not the constraint of the task, but the negative space around it. For Camus, it was the fact that Sisyphus could do whatever he wanted while he returned to the bottom of the hill that was the most important part. He could create his own meaning and joy within a situation that was ultimately pointless. This is also why Camus never killed himself when other existentialists did.

In The Republic, in the famous allegory of the cave, Plato nicely illustrates Socrates’ theory of the forms. The shadows on the wall mimic reality, but are not reality, in the same way that what we see in the world is merely a representation of the form of something. Look around you, find a square. For Socrates there is a form of the square that simply exists, in the abstract. It is unchanging, pure, and fundamental.

The work of Piet Mondrian, and indeed of the entire De Stijl movement, can be read through the lens of these two philosophical building blocks - for De Stijl is simultaneously an exercise in constraint, and an exercise in fundamentals. Indeed, we see an analog with brutalism, though while brutalism emphasized the material (the stoneness of the stone) De Stijl strongly emphasizes the component parts of the visual world. Blacks and whites, primary colors, straight lines and basic geometry. All can be built with this, yet we rarely strip away the decoration to examine the core underneath.

This was Mondrian’s project, to find the core, the essential elements, the forms of expression. While his later work is immediately identifiable, looking back at his earlier work and you can see how he played with constraint in a search for the fundamental elements of expression:

(Piet Mondrian, “The Red Tree” - c1908-1910. Photo: WikiCommons.)

Consider the red tree, completed about a decade before the De Stijl movement was established. Already we see the constraints of primary colors, transforming what is (to be honest) a fairly unremarkable subject and portrayal into something worthy of our attention. But the focus on primary colours was not enough for Mondrian, who added additional (and harsher) constraints. Consider 1911’s The Red Mill, which maintains the constraint of the primary color scheme, but is also constructed almost entirely with straight lines at hard angles to one another.

(Piet Mondrian, “The Red Mill” - 1911. Photo: WikiCommons)

The movement to constraint and colour didn’t happen simultaneously, but Mondrian experimented with both as he tried to get closer to the ideal.

Piet Mondrian, “Still Life with Gingerpot II” - c1911-1912. Photo: WikiCommons.)

Take Still Life with Gingerpot II, which reduces the still life form to hard lines and solid colours - blues and yellows and shades of grey. The movement toward the ideal and the ability to find expression in constraint finally get entangled in Mondrian’s work that came to be associated with the De Stijl movement: his simply titled Compositions.

(Piet Mondiran, “Composition A” - 1920. Photo: WikiCommons.)

Earlier work, such as Composition A, emphasized the use of color, and de-emphasized the lines that divided them (note how the black lines fade as they near the edge of the canvas). And while asymmetrical, the work is not aggressively so. The yellow and blue spaces at the bottom right could be the same size, as could the two white spaces in the middle. His later work is more interesting, dropping the colors in order to emphasize the importance of what isn’t there, stressing the importance of the lines.

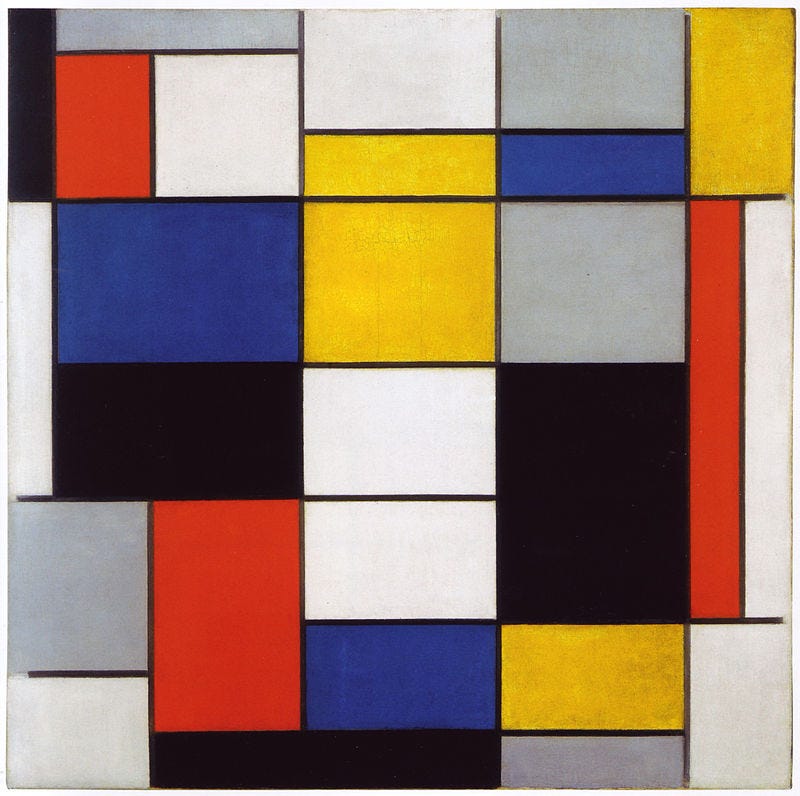

(Piet Mondrian, “Composition with Red, Yellow, and Blue” - 1928. Photo: WikiCommons.)

Composition with Red, Yellow, and Blue is notable for a few reasons. First, notice the name. Previous works were composition in Red, Yellow, Blue, and Black. The subtle shift brings more attention to the composition itself - what matters is how this image is constructed, how the pieces fit together, and how they relate. Second, note the texture in the white space. The black lines are solid, the colors are brush strokes in a single direction, but the white space is layered, textured, complex. Mondrian had found an additional avenue for expression within the rigid constraints of pure composition.

This was Neoplasticism - the constraint of primary colors, of two directions (horizontal and vertical), and of three simple modes (black, white, and gray). For Mondrian, this was the pure language of aesthetics, and all could be produced and represented through these components. His commitment to this is understandable when seen through the lens of Camus and Socrates: it is the reduction to forms, and the imposition of constraint that allows for the closest approximation of the ideal. But it didn’t endure him to his De Stijl co-founder, Theo van Doesburg, who found value in reducing constraint (diagonal lines?! fuck off!). It’s tempting to look at Van Doesburg’s appropriately named Counter Composition V, as a response to Mondrian’s rigidness, but it can also be seen as a challenge to the elemental forms. Indeed, a diamond is merely a square slightly turned, and indeed Mondrian seems to have recognized this at least in principle in his Lozenge work and his incomplete Victory Boogie Woogie. Mondrian named his pieces quite purposefully, and this piece embraces the use of triangles and diamonds, as well as a crude pointillism, where large pixels combine to create new colours, shapes and textures. Was this piece for Van Doesburg? Was it his “victory dance”? And was it left unfinished on purpose?

(Piet Mondrian, “Victory Boogie Woogie” c1942-1944. Photo: WikiCommons.)